The promise of Text-to-SQL is compelling: let anyone query a database using plain English. The reality is that most implementations silently return wrong data, expose sensitive information, and cost more than they should.

TL;DR: The naïve approach to Text-to-SQL is to stuff the entire schema into a prompt and ask the LLM to generate SQL. While it works for 3-to-5 table demos, on a 35-table emulated-enterprise-level schema, it produces silent wrong results, generates destructive SQL, exposes PII with no access control, and sends the entire schema on every query. This post demonstrates each failure mode with code and output against a PostgreSQL database.

The Promise

Vast amounts of business logic and data are locked in databases, accessible only through analysts and engineers. This creates bottlenecks in decision-making. A marketing manager asking “What were the sales in the Northeast last quarter for product X?” shouldn’t need to file a Jira ticket and wait three days.

Text-to-SQL aims to democratise data access: translate a natural language question into SQL, execute it, and return the answer. In theory, this eliminates the bottleneck. In practice, the engineering challenge is significant.

It is not just a prompt engineering problem.

- It is a reliability challenge → hallucinated SQL produces wrong business decisions

- It is a security challenge → preventing access to PII tables and blocking destructive operations

- And it is a scalability challenge → handling diverse query patterns across hundreds of tables without sending the entire schema on every request

The Setup: 35-Table Emulated-Enterprise-Level Schema

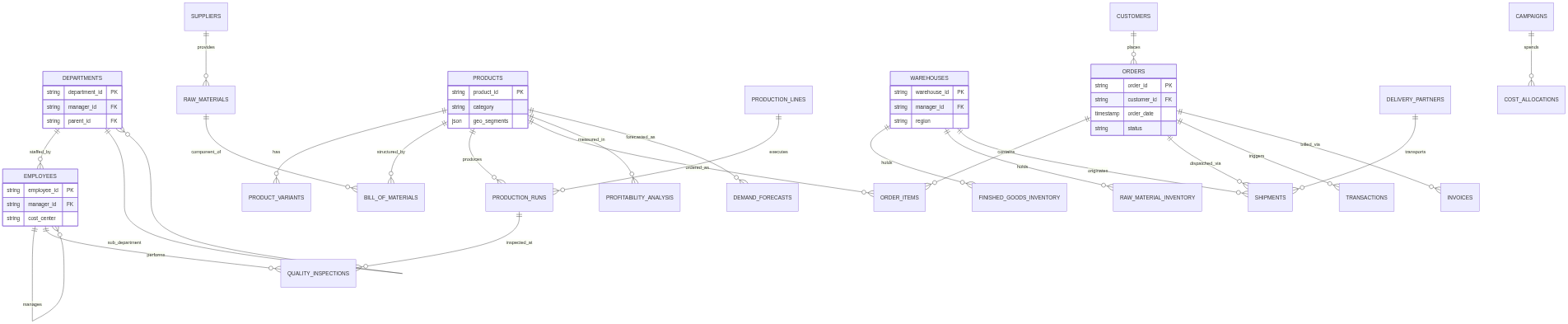

To test this properly, basic users and orders table will not do. I built a 35-table schema modelling an emulated manufacturing and e-commerce company across 7 domains across a few geographies:

| Domain | Tables | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | 8 | products, suppliers, BOMs, production runs, quality inspections |

| Inventory | 7 | finished goods, raw materials, safety stock, valuation |

| Logistics | 5 | warehouses, shipping routes, shipments, customs |

| E-commerce | 4 | customers, orders, order items, returns |

| Analytics | 5 | sessions, campaigns, funnels, CLV, demand forecasts |

| Finance | 4 | transactions, invoices, cost allocations, profitability |

| HR | 2 | employees, departments |

This schema includes cross-domain relationships, geographic constraints, generated columns, and the kind of complexity that real enterprise systems have. The full schema and sample data are in the companion repository.

Why PostgreSQL, Not SQLite

For the code associated with this blog post, Neon, a serverless PostgreSQL provider is used, rather than SQLite.

- While SQLite is convenient for prototyping, enterprise Text-to-SQL systems target production databases such as PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server - and the SQL dialect differences matter

- Neon provides a PostgreSQL instance with zero infrastructure management: no Docker, no local installation, just a connection string

- One could equally use Google Cloud SQL, AWS RDS, or Azure Database for PostgreSQL - the code requires only a connection string change

The Naïve Approach

The entire implementation fits in about 50 lines:

SYSTEM_PROMPT = """You are a SQL assistant. Given a PostgreSQL database schema,

generate a SQL query that answers the user's question.

Return ONLY the SQL query, no explanations, no markdown."""

def ask(question: str) -> list[dict]:

# Step 1: Load the ENTIRE schema as context

schema = get_schema_ddl()

# Step 2: Ask the LLM to generate SQL

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-4o-mini",

messages=[

{"role": "system", "content": SYSTEM_PROMPT},

{"role": "user", "content": f"Schema:\n{schema}\n\nQuestion: {question}"},

],

temperature=0,

)

sql = response.choices[0].message.content.strip()

# Step 3: Execute the SQL directly — no validation whatsoever

return execute_query(sql)

That is it!

Load schema, prompt LLM, execute raw SQL, return results.

🚨️ No validation, No safety, No guardrails

This is what most Text-to-SQL demos show, and this is exactly what breaks in production!

What Works, And Why

Simple, single-table queries work reliably:

👩🏼💼 User: Show all active products in the Electronics category

// Generated SQL

SELECT * FROM products

WHERE is_active = TRUE AND category = 'Electronics'

// Results: 3 rows ✓

Even straightforward joins work:

👩🏼💼 User: How many different raw materials does each supplier provide?

// Generated SQL

SELECT

s.supplier_name,

COUNT(rm.material_id) AS material_count

FROM suppliers AS s

INNER JOIN raw_materials AS rm ON s.supplier_id = rm.supplier_id

GROUP BY s.supplier_name

// Results: 5 rows ✓

This is where many demos stop. 3-5 tables, simple queries, everything looks promising. Let’s progressively take things up a notch till things start to break.

Scenario S04: 3-table join, single domain

Taking it up a notch, asking a question which requires a 3-table join, single domain (manufacturing):

👩🏼💼 User: Show the quality inspection pass rate for each production line, including the line name and location

// Generated SQL

SELECT

pl.line_name,

pl.location,

COUNT(qi.inspection_id) AS total_inspections,

SUM(CASE WHEN qi.passed THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) AS passed_inspections,

(

SUM(CASE WHEN qi.passed THEN 1 ELSE 0 END) * 100.0

/ COUNT(qi.inspection_id)

) AS pass_rate

FROM production_lines AS pl

LEFT JOIN production_runs AS pr ON pl.line_id = pr.production_line_id

LEFT JOIN quality_inspections AS qi ON pr.run_id = qi.run_id

GROUP BY pl.line_name, pl.location

// Results: 3 rows ✓

All scenarios referenced in this post are in the test suite accompanying this series of blog posts.

Scenario S05: 3-table join, cross-domain

Next, asking a question which requires a 3-table join, cross-domain (Manufacturing + E-commerce).

👩🏼💼 User: Show total units sold per product variant, with the product name and variant SKU

// Generated SQL

SELECT

p.product_name,

pv.sku,

SUM(oi.quantity) AS total_quantity_sold

FROM order_items AS oi

INNER JOIN products AS p ON oi.product_id = p.product_id

INNER JOIN product_variants AS pv ON oi.variant_id = pv.variant_id

GROUP BY p.product_name, pv.sku

// Results: 10 rows ✓

Why this works:

- Crosses domain boundaries (Manufacturing → E-commerce) yet succeeds because FK path is unambiguous, i.e. each FK points to exactly one target table

- LLM does not need to choose between competing join paths

- Failures begin when multiple join paths exist and the LLM must judge which is correct

Scenario S06: 3-table join with subquery and comparison logic

Next, asking a question which requires a 3-table join with subquery and comparison logic (Inventory + Manufacturing)

👩🏼💼 User: Which products in the Singapore warehouse have available inventory below their safety stock reorder point?

// Generated SQL

SELECT

p.product_name,

fgi.available_quantity,

ssl.reorder_point

FROM finished_goods_inventory AS fgi

INNER JOIN products AS p ON fgi.product_id = p.product_id

INNER JOIN safety_stock_levels AS ssl

ON

fgi.product_id = ssl.product_id

AND fgi.variant_id = ssl.variant_id

AND fgi.warehouse_id = ssl.warehouse_id

WHERE fgi.warehouse_id = (

SELECT warehouse_id FROM warehouses

WHERE country = 'Singapore'

)

AND fgi.available_quantity < ssl.reorder_point

Why this works:

- LLM resolves “Singapore warehouse” to a subquery on

warehouses - Correctly joins on a composite key (product_id + variant_id + warehouse_id)

- FK paths remain unambiguous despite the added complexity

Scenario S07: 3-table join with column name disambiguation

Next, asking a question which requires a 3-table join across E-commerce and Logistics, where the FK column name doesn’t match the PK it references.

👩🏼💼 User: Show all customers who have had shipments delivered, with the delivery partner name and shipping cost

// Generated SQL

SELECT

c.first_name,

c.last_name,

dp.partner_name,

s.shipping_cost

FROM customers AS c

INNER JOIN shipments AS s ON c.customer_id = s.to_customer_id

INNER JOIN delivery_partners AS dp ON s.partner_id = dp.partner_id

WHERE s.status = 'delivered'

ORDER BY s.shipping_cost DESC

// Results: 8 rows ✓

Why this works:

- Three tables across two domains (E-commerce + Logistics):

customers,shipments,delivery_partners - LLM correctly picks

to_customer_id(notcustomer_id) onshipments— column name disambiguation - Correctly translates “delivered” from the question into

WHERE s.status = 'delivered' - Still succeeds because each FK has only one plausible target

All six queries succeeded because the join paths were unambiguous. Each FK relationship led to exactly one reasonable table. The LLM didn’t need to choose between competing interpretations. Watch what happens when queries span multiple domains simultaneously, where multiple join paths exist, or where business context is required to pick the right one.

Where It Breaks

Failure Mode 1: Silent Wrong Results

🚨️ This is the most dangerous failure because there is no error

The SQL executes, results return, and they look plausible, however the numbers are wrong.

🧑🏼💼 Decision Maker: Show total revenue by product category, but only for products that have been manufactured on a Singapore production line

Here is what the naïve approach generated:

// Generated SQL

SELECT

p.category,

SUM(pa.revenue) AS total_revenue

FROM products AS p

INNER JOIN production_runs AS pr ON p.product_id = pr.product_id

INNER JOIN production_lines AS pl ON pr.production_line_id = pl.line_id

INNER JOIN profitability_analysis AS pa ON p.product_id = pa.product_id

WHERE pl.location = 'Singapore'

GROUP BY p.category

ORDER BY total_revenue DESC;

The SQL is valid. It executes without error. It returns a clean result:

| category | total_revenue |

|---|---|

| Electronics | $271,049.20 |

Looks reasonable, right? It is wrong. The correct answer is $154,050.10.

$154,050.10 (actual) versus $271,049.20 → the naïve approach inflated revenue by 76%.

What went wrong? Product P-1001 has 2 production runs on the Singapore production line (RUN-2024-001 and RUN-2024-002). Joining production_runs without DISTINCT causes every profitability_analysis row for P-1001 to get duplicated (once for each production run), as a result the revenue for P-1001 is counted twice.

The correct SQL needs a DISTINCT on product_id after filtering by Singapore production lines, then joins to revenue data. But the naïve approach has no awareness of this trap.

👉 The result looks like a valid table of numbers. Nothing flags that the revenue figure is 76% higher than it should be. A decision maker would make a wrong decision based on this data.

🚨️ No golden dataset to validate against, No evaluation framework to flag that the revenue figure diverged from ground truth

The naïve approach has no way to know it is wrong.

In Part 2 (will be published soon), I introduce a verification step using golden query-answer pairs for regression testing.

Failure Mode 2: Unsafe SQL

The LLM generates whatever SQL matches the intent. Including destructive operations:

🦹🏼 Malicious Actor (impersonator): Delete all customers who’ve not ordered in last 6 months

// Generated SQL

DELETE FROM customers

WHERE

customer_id NOT IN

(

SELECT DISTINCT customer_id FROM orders

WHERE order_date >= CURRENT_DATE - INTERVAL '6 months'

)

🦹🏼 Malicious Actor (impersonator): Update all product prices by increasing them 15%

// Generated SQL

UPDATE products SET manufacturing_cost = manufacturing_cost * 1.15

👉 These are syntactically correct, semantically valid SQL statements. The naïve implementation would execute them.

🚨️ No read-only enforcement, No write-blocking, No confirmation step

Failure Mode 3: No Access Control

Any user can query any table.

👩🏼💼 User (marketing analyst): Show me all customer emails, phone numbers, and their lifetime value

// Generated SQL

SELECT

email,

phone,

lifetime_value

FROM customers

ORDER BY lifetime_value DESC

// Results: 10 rows of PII returned without restriction

👩🏼💼 User (marketing analyst): Show all supplier payment terms and reliability scores

//Generated SQL

SELECT

s.supplier_name,

s.payment_terms,

s.reliability_score,

rm.material_name,

rm.unit_cost

FROM suppliers s

JOIN raw_materials rm ON s.supplier_id = rm.supplier_id;

// Results: Procurement-sensitive competitive intelligence exposed

🚨️ No RBAC (role-based access control), No PII masking, No data classification

👉 The naïve approach treats every user as a database administrator.

In Part 2 (will be published soon), I introduce a Security Agent with veto power that enforces role-based access control.

Failure Mode 4: Ambiguous Natural Language

Natural language is inherently ambiguous, and the LLM resolves ambiguity silently

🚨️ it picks an interpretation and generates SQL without asking for clarification

An example,

👩🏼💼 User: What are our best-selling products?

// Generated SQL

SELECT

p.product_id,

SUM(oi.quantity) AS total_sold

FROM products AS p

INNER JOIN order_items AS oi ON p.product_id = oi.product_id

GROUP BY p.product_id, p.product_name

ORDER BY total_sold DESC

// Results:

// Product ID P-1005 101

// Product ID P-1003 72

// Product ID P-1001 52

// Product ID P-1004 50

// Product ID P-1006 4

// Product ID P-1002 2

The LLM silently picked “best-selling = highest quantity sold”. The answer looks correct → and it is correct for that interpretation.

But another decision maker (say A, a finance director) may ask the same question with the expectation that “best-selling = highest revenue”. That gives a completely different #1 ranked product:

| By quantity (LLM’s pick) | By revenue (equally valid) | |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | Product ID P-1005 - 101 units | Product ID P-1001 - $72,499 |

| #2 | Product ID P-1003 - 72 units | Product ID P-1003 - $9,359 |

| #3 | Product ID P-1001 - 52 units | Product ID P-1005 - $5,049 |

- P-1005 sells 2x more units but generates 14x less revenue than P-1001

- Another decision maker (say B, a supply chain manager) reading the LLM’s answer would stock up on P-1005

- Decision maker A would prioritise P-1001

👉 Same question, opposite decisions; and the LLM never asked which interpretation the user intended

Failure Mode 5: Context Window Cost

The full 35-table DDL is approximately 8,414 tokens. Every single query sends the entire schema as context.

| Scale | GPT-4o-mini ($0.15/1M) | GPT-4o ($2.50/1M) |

|---|---|---|

| Per query | $0.0013 | $0.0210 |

| 100 queries/day | $0.13/day | $2.10/day |

| 10,000 queries/day | $12.62/day | $210.35/day |

And this is only 35 tables

- Enterprise systems have 200-500+ tables

- At 500 tables, the schema exceeds most models’ context windows entirely → the naïve approach simply cannot work

🚨️ The Hidden Cost: Token Waste

Let’s quantify the waste. Using one of the simplest queries, S01, a single-table filter, in the test suite accompanying this series of blog posts:

👩🏼💼 User: Show all active products in the Electronics category

//Generated SQL

SELECT * FROM products WHERE is_active = TRUE AND category = 'Electronics';

The response (generated SQL) consumed just 16 tokens. How many tokens were sent to get it? 8,414!

| Context strategy | Input tokens | vs. Full schema | vs. Answer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full schema DDL (naïve approach) | 8,414 | — | 526x |

| CREATE TABLE blocks only | 5,230 | 38% less | 327x |

| Only the products table | 166 | 98% less | 10x |

👉 To generate 16 tokens of SQL, the naïve approach sends 8,414 tokens of context → a 526:1 ratio. And this is just a 35-table schema. Enterprise systems routinely have 200–500+ tables.

- Even a simple optimisation (such as removing comments, DROP statements, and operational commands from the DDL) saves 38% of tokens

- An approach that selects the right table/s (in this case, this query only needs the

productstable) could achieve a 98% reduction

This is exactly the kind of schema-aware context selection that I cover in Part 2.

You can reproduce these numbers yourself:

python demos/02_token_waste_analysis.py

- The script

02_token_waste_analysis.pyusestiktokento estimate the token usage. The actual numbers from the API differ slightly fromtiktoken’s local estimate

The Cost of Getting It Wrong

These failure modes are not hypothetical, and start to surface once dealing with >20 tables across domains.

In a production environment, these failure modes compound:

-

Wrong data → wrong decisions. An inflated revenue report doesn’t just mislead one analyst → it triggers misinformed decisions → by the time someone questions the number, downstream decisions are already in motion

-

No safety → data loss. A single destructive query can delete production data. Recovery from backup is hours of downtime

-

No access control → compliance failure. Exposing customer PII violates GDPR, PDPA, and similar regulations. The fines are real.

Under PDPA and GDPR, the data controller is liable regardless of whether the exposure was intentional. Here “the LLM did it” will NOT be a defense.

- Ambiguous resolution → erosion of trust. When users get inconsistent answers to the same question, they stop using the system. The investment is wasted

Once business users get contradictory answers to the same question, they revert to filing tickets with the data team → the Text-to-SQL investment delivers negative ROI → you’ve spent the money and added a system nobody trusts.

What’s Next

The goal is not to build a chatbot that writes SQL. The goal is to build a trusted data access layer that translates natural language into safe, efficient, and accurate data queries.

The naïve approach treats Text-to-SQL as a single task: prompt in, SQL out.

In practice, it’s at least four distinct responsibilities → understanding intent, selecting relevant schema, generating safe SQL, and validating results. Each requiring different logic and different failure handling.

This blog post (part 1 of a multi-part series) just introduced the various gotchas of taking the naïve approach.

In Part 2 (will be published soon), I solve these problems with an agentic architecture: multiple specialised agents, including a Security & Governance Agent with veto power → that validate, guard, optimise, and explain every query before it touches the database.

In Part 3 (will be published soon), I red-team the Security & Governance Agent using multi-turn attacks → only to discover additional uncomfortable truths and cover a few defensive measures with implementation details.

In Part 4 (will be published soon), I cover MCP integration - enabling dynamic schema discovery and tool orchestration across data sources.

ℹ️ Version History

- 18 Feb 2026 : Post published